Adapting Land Value Taxation to Space

Source: SFI

Adapting Land Value Taxation to Space

Source: SFI

Taxation and Space

Taxation is Essential to Governance

Taxation finances the modern state and makes it possible for governments to supply public goods, insure risks, shape behavior, and make economic activity legible to the public. In order to establish effective government in space, tax policy must be adapted to the celestial realm.

With the proliferation of space enterprise, it’s worth considering how to govern activities in earth’s orbit and beyond. A proper framework for space governance can increase coordination between actors and ensure enforcement of fair policies in space. In particular, a tax regime that promotes growth while limiting winner-take-all dynamics can mitigate inequality and diffuse international tensions over the ownership of space.

Space taxation is currently a neglected topic, and early legal regimes tend to be sticky, which suggests that establishing taxation systems in tandem with the development of an orbital economy would be valuable.

For concreteness, consider the following scenario:

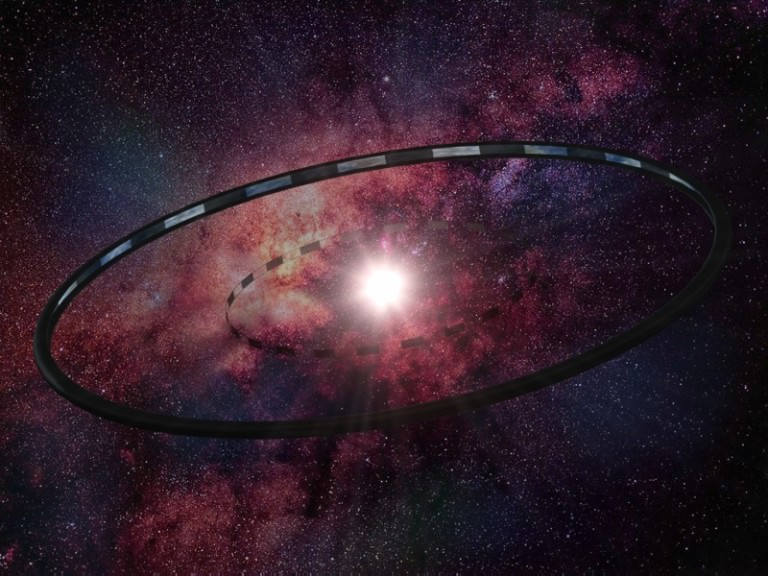

The Alpha Centauri system is united under a single government, and wishes to build a large magnetic ring structure for starlifting. The project is too expensive for private investment and requires state protection to avoid theft of components during construction. But the state needs to buy materials and contract labor from citizens. How do they equitably raise revenues to fund a project that can benefit the entire system?

This is a natural case where some form of taxation should be used to support the project. Done properly, taxes can be used for local public goods or redistributive efforts. However, care must be taken when designing the tax system. Inefficient taxes can be a drag on the economy, and unfair taxes threaten the legitimacy of the tax authority.

Principles of Taxation

When considering how to design taxes in accordance with good governance, there are several important principles to consider.

Efficiency: Many types of taxes create economic inefficiencies (i.e. deadweight loss), which means that they generate less revenue than the costs they impose. Though it’s difficult to implement perfectly efficient taxes, it’s critical that taxes do not hinder economic growth too much. When in doubt, policymakers should err towards lower levels of taxation.

Sufficient Revenue: Taxes should produce enough revenue to provide important public goods. Otherwise, the effort of raising and spending taxes will be wasted.

Practical: It should be feasible for the tax authority to assess, collect, and disburse taxes. Some taxes may seem sound, but turn out to be impossible to assess, especially when considering how citizens change their behavior to evade the tax. Furthermore, collecting tax revenues comes at significant costs, and policymakers must ensure that these costs do not eat up a substantial fraction of revenues.

Tolerable: Taxes should be unobtrusive, fair, and consistent over time. Taxes that are intolerable for citizens will not last long, regardless of their other benefits.

Clear: Citizens should be able to easily determine how much they will have to pay now and in the future.

Local: Taxes should be sensitive to the boundaries of local public goods. It would be unjust to raise funds for local infrastructure by taxing individuals on the other side of the galaxy. As such, taxes should be spent on projects close to where the funds were gathered, particularly from those who stand to benefit most.

Georgism as a solution to taxation in space

Unlike on earth, nobody has a clear claim to the resources in space. The Outer Space Treaty declares that “[o]uter space … shall be free for exploration and use by all States…” but leaves out many legal details. If we were to allow individuals to claim parts of space, what is the fairest way to assign ownership? Ideally this policy would encourage the appropriate use of resources and redistribute at least some of the gains from orbital enterprise.

Weak property rights in space would mean that there is little incentive to invest or innovate making it difficult to fund exploration efforts. Recognizing this, some states have passed laws to support the growth of the space industry.

However, excessively strong property rights can lead to a different affliction. Namely, people are incentivized to buy and hold large swathes of land, speculating that they will become valuable in the future. With no cost of holding land, owners will wait for others to develop land nearby and raise the rent they can charge. This creates a race to possess land in space, and encourages owners to leave land undeveloped.

Georgism presents a balanced solution: individuals are granted strong property rights, but are discouraged from rent-seeking. Henry George advocated for land value taxes proportional to the rent that could be generated from owning an empty lot in the same location. An empty lot in the center of a thriving city can charge more rent than a plot in the middle of nowhere. This tax on “ground rent” encourages owners to develop the land. George advocated for similar taxes based on the principle that individuals who take possession of natural resources must pay society for the unamended value of those resources. Later sections will describe these in more detail.

George also advocated for excess taxes not spent on public goods to be returned to the public in the form of a “citizens dividend” which can be used to share the gains from economic growth.

Georgist or land value taxes meet all of the desired data for a tax system as they are fair, efficient, raise significant amounts of revenue, and are straightforward to assess. This is a strong reason to apply the Georgist approach to taxation in space. Here, we will consider how Georgism might be applied to stellar governance.

Applying the Georgist Paradigm in Space

Taxing Natural Resources in Space

The physical resources in space can be roughly divided into useful energy and matter.

Let’s start with energy. Since there is a fixed amount of useful energy in the universe, energy is an exhaustible resource. In this case, the Georgist framework would suggest a severance tax, where individuals who extract energy from natural sources pay a unit cost.

Matter is different. Since atoms can technically be recycled, they bear a resemblance to plots of land that you can reuse or loan to others. The Georgist tax would be proportional to the rental value of certain types of matter.

When taxing materials use, care must be taken to avoid distorting incentives. It may be tempting to tax valuable carbon fiber more than cheap graphite, but since they are made from the same element, this would discourage the production of carbon fiber! Distortions arise when different arrangements of the same elements are taxed differently, favoring certain combinations over others. The lesson here is that taxes on matter cannot depend on the structure of the material, only its composition.

There are some other difficulties with taxing matter. In the future, it may be feasible to transmute some elements into others. Assuming this process is cheap enough, this would create elasticity in the supply of different elements, breaking the assumption that the supply of certain elements is inelastic like land. This means that taxes on matter will have to remain low in order to avoid distortions.

Einstein’s famous equation E=MC^2 suggests it may also be possible to cheaply convert matter into energy (or vice versa) in the future, which creates elasticity of supply in both matter and energy, meaning that the taxes on each will have to be reduced to avoid distortions.

To avoid these problems, it may be simpler to tax mass-energy as a single unit, which also has the benefit of being easy for authorities to estimate.

Note that the definition of natural resources in space may change significantly in the future. Interstellar civilizations may find uses for more exotic natural resources such as dark matter, dark energy, fundamental particles, or antimatter. In each case, tax policy will need to determine how to encourage appropriate use of these resources without creating distortions.

Taxing Land in Space

Physical space is more straightforward to tax. It’s analogous to land, and owners can be taxed proportional to the rental value. Plots of land on a particular planet would be subject to a standard land value tax.

In the future, colonies at Lagrange points may also be subject to a land value tax. Lagrange points may become important centers of economic activity in the future given their stability and proximity to a particular planet. Ownership in these regions may be defined by 3 dimensional coordinates relative to the center of the Lagrange point and assessed based on the value of nearby colonies (see note).

Assessment may be more difficult for space colonies with varying geometries, but the principle remains the same; owners are taxed based on the rent they could charge for the undeveloped region they possess.

Besides proximity to economic activity, direct access to sunlight will have a large effect on property values as it gives owners a consistent source of energy. New forms of “sun rights” will have to be developed to prevent structures from blocking an owner’s access to sunlight.

Other Important Resources

Some resources don’t fit the description of land or natural resources but still exhibit rivalry in their use. George advocated for the management of all “natural forces and opportunities”, not just land and minerals.

Broadband spectrum is one such “opportunity” that multiple individuals cannot use simultaneously. Today, the rights to different bands of the spectrum are auctioned off in exchange for exclusive rights to the frequency band. This accords with Georgist principles as it requires owners to pay the public based on the value of exclusive access. These communication bands will be critical to use in space and will need to be apportioned in a similar way.

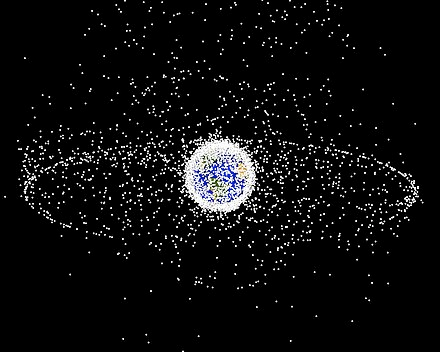

Orbits are another rivalrous resource that requires management. Valuable orbits such as GEO have limited space to accommodate satellites and users should pay for their right to use these orbits. Similar to spectrum, slots can be auctioned off at regular intervals, with the proceeds going to a citizen’s dividend or public projects.

Other situations may arise where many users compete for access to certain rights-of-way, creating congestion. Where possible, tolls similar to road pricing can be used to reduce congestion.

Each celestial body will have associated orbits, communications bands, and other congestible resources. Georgist policies will have to be extended to the particulars of each situation, ensuring that users pay a fair price for exclusive use of such scarce resources.

Pigouvian Taxation

Taxing externalities is used to discourage negative-sum activities such as pollution. In space, there are several important externalities to take into account. Many of the fees in the previous section designed to reduce congestion can be thought of as a tax on “congestion externalities”.

Orbital debris is a particularly damaging form of pollution in space which can destroy satellites. At an extreme, the cascading effects of space junk can lead to Kessler Syndrome, making entire orbits unusable . To reduce the production of such debris, states will have to heavily fine individuals who generate orbital debris and fund cleanup efforts.

Other Considerations

Limitations on tax technology

In their history of tax systems, Joel Slemrod and Michael Keen highlight the constraints on a tax system set by existing “tax technology”. A state without the capacity to measure the wealth or income of an individual will have a hard time taxing them appropriately.

Looking towards the future, strong physical limitations prevent certain forms of taxation in space. For example, the speed of light limits how quickly information can travel, and will make it difficult to administer a state over large distances.

The absolute number of citizens and places important constraints on tax technology. The resources of the solar system and beyond may support many billions of individuals in the far future. Additionally, many activities in space may be carried out by autonomous robotic systems. With this in mind, it’s important to consider whether ownership records can feasibly be extended to this scenario. It may not be cost-effective to track land ownership and resource extraction across billions of individuals using trillions of robotic systems; these difficulties may force tax authorities to splinter into more localized states, or focus the burden of taxation on the most valuable land.

It may also be infeasible to tax many smallholders, identify who is using sunlight, or track extraction of resources from small asteroids. In these cases, the costs of enforcement will make collection impractical. Instead, states can focus on large property owners, corporations engaged in resource extraction, or build centralized infrastructure for trading natural resources; charging users bringing goods to market.

Land Value Assessment

Assessing the rental value of a property is essential to land value. It can be difficult to determine the value of pure land independent of the property built upon it. There are many proposals to solve this problem, I present a few illustrative cases.

Direct Assessment: Here, tax authorities employ professional land value assessors to determine the rental value of every property. This is more feasible than it sounds, most property assessments today separately report the value of the land and the buildings on top. This approach has the benefit of being simple and accurate, and was endorsed by Henry George himself. However, in space, it may be prohibitively expensive to send land assessors across the solar system.

Harberger Taxation: Rather than independently assess the value of a property, we can require individuals to self-assess the value of their land and tax them proportionally. To prevent underreporting, the state requires that owners be willing to sell their land for the declared price. If the tax rate is set correctly, this leads owners to declare their true valuation of the land. Harberger taxation is much simpler to implement than direct assessment while still providing accurate land valuations. This comes at the cost of reduced investment efficiency; when owners are uncertain that their property will be bought by someone else, they have less incentive to invest in long term improvements. This could be particularly detrimental in space, where projects need long time horizons to justify investment. It’s possible to recover investment efficiency somewhat by guaranteeing longer ownership terms or creating systems for owners to repurchase their land at the new market price.

Land Auctions: I have proposed an alternative assessment scheme which requires any sale of land to occur at public auction, separate from the sale of any structures built upon the land. The auction value is then used as the basis for the tax. Public auctions are simple, and because owners can choose when to sell their land, there is no loss of investment efficiency. However, because land and amendments are not perfectly separable, the auction value differs from the true land value. In space settlements where built structures can easily be removed (such as L5) this may not pose much of a problem. For settlements where removing amendments is prohibitively expensive, this may be an issue.

The right approach to assessment will vary depending on the situation and the asset being taxed. Some approaches may be infeasible or the particular distortions they induce may be detrimental to certain markets. Tax law will need to adapt to each area, ensuring that policy is consistent with the principles of taxation above.

Public Utilities and Monopoly

Today, some sectors of the economy have network effects giving rise to natural monopolies. For example, electrical grids are more efficiently operated by a single entity that connects many individuals.

However, once formed, these monopolies can collect rents, which must be carefully regulated. George advocated for municipalization of such monopolies, allowing many competitors to provide services over the same network.

In space, states may build or municipalize transport hubs, charging usage fees similar to the gate fees paid by airlines today. The same approach may be necessary when building system-wide energy infrastructure, landing pads, and communications systems.

Monopolies on critical resources such as water present a similar challenge, allowing corporations to unfairly collect resource rents. The adverse physical characteristics of outer space and scarcity of critical resources may promote the formation of unfair monopolies. States should take steps to encourage new entrants to monopolized industries and consider municipalization or the dissolution of important resource monopolies.

Financing Development

In the future, various stakeholders will share an interest in developing outer space. For example, a multinational coalition may wish to create a Martian colony.

The tax revenue generated by a successful settlement would be substantial. This coalition could finance its development by promising creditors a share in the future tax receipts.

Alternatively, founders can offer certain individuals a portion of regional tax revenues. These individuals will then have an incentive to develop the land and can raise capital by borrowing on their future revenue.

Land value taxes further encourage development by incentivizing landowners to use their land rather than let it lie fallow.

Maximizing Growth

There are some subtleties to implementing tax policy in space. It’s important not to set taxes too high to maintain incentives to search for new sources of energy, matter and land.

In particular, some parts of the universe can end up outside of our light cone if growth proceeds too slowly, so it’s important that these taxes do not reduce the rate of expansion. Faster colonization leads to more total resources and a larger citizens dividend. Even small changes in the growth rate can have astronomical effects in the long run.

Tax policies must strike a careful balance; if colonization is taxed heavily, then it will slow growth; but if colonization is rewarded too much, excess capital will be devoted to expansion rather than local development, which can also slow growth.

Conclusion

Tax administration will likely remain a crucial part of governance even as humanity spreads to the stars. Taxation is inevitable, even in space. However, tax policy will have to adapt to this new context in order to increase growth, provide public goods, and share the gains from interstellar expansion.

Careful application of the Georgist paradigm can accomplish these goals simultaneously. It advocates for land value taxes, fees for the extraction of natural resources, and spectrum auctions, among other things.

Future technologies play a critical role in shaping tax policy in space; new technologies can make taxes easier to assess or easier to evade. Newly discovered physics may change our definition of economic land; staying ahead of these developments can ensure tax administration remains effective and fair.

Designing better tax systems in space can help shape space governance, ensuring that it is both effective and fair. However, more research needs to be conducted on how our space taxation system should be designed. Questions remaining include the functioning of the citizens dividend, implementation details for the taxation of various resources, the process for creating a space taxation framework, and legal considerations of appropriation and ownership in the long-term future.

Note

Note that putting significant mass in a Lagrange point can cause them to change position. For example, if a significant amount of mass gets added to Earth-Moon L5, policymakers may want to limit the mass of additional construction to avoid changing the position or destabilizing the Lagrange point.